Theatre Consultants

Who We Are and What We Do

Introduction

Whether you call us theatre planners, theatre designers or theatre consultants, we are professionals who design theatre spaces and their systems, and guide the architectural design team throughout the theatre design process. We collaborate with the owner and users to establish the functional requirements of the theatre, and with the architect and engineers to ensure that the building provides for and supports those requirements. Theatre planners are essential members of the team designing or renovating any theatre, concert hall, amphitheater or other performing arts venue.

Theatre planners are specialists with expertise in three worlds - performing arts production, architecture and construction. The most obvious part of theatre planning is designing and documenting the theatre's special requirements - the form and layout of the theatre, space adjacencies, stage rigging, dimming and control, seating, etc. In addition, designing a performing arts space requires extensive collaboration between the owners/users and the design team. The theatre planner, who is fluent in the languages of both groups, facilitates that collaboration. By assisting and guiding the collaboration theatre planners help to assure a successful project for everyone.

Determining the Scale + Scope of a Project

The early part of the work in a new theatre building involves understanding and planning the project. This includes determining which spaces are needed, their adjacencies and the project's budget. Some of the typical steps a theatre consultant will take or contribute to are:

Assist in creating the building program.

Develop the budget for theatre infrastructure and equipment.

Lead discussions on the relationship between the performers and the audience to determine the form of the theatre, if that is not already known.

Plan and design the stagehouse and all theatre systems described below.

Collaborate with the users and the architect on backstage planning and design including dressing rooms, rehearsal rooms, shops, storage and loading docks.

Collaborate with the users and the architect on front of house planning including ticket booths, concessions, coat rooms and other audience amenities.

Theatre Systems Design + Specification

Once the outline of the building and the production requirements are understood, the theatre planner will begin to design, draw, and specify the systems. These systems may include any or all of the following:

Seating Layout and Seat Selection Design the arrangement of seats, wheelchair locations, aisles, balcony heights and sizes. This includes studying the sightlines in section to assure that everyone has a good view of the stage. Collaborate on selecting the seat, its components and finishes.

Stage Rigging System Discuss the stage rigging requirements with the owner and users to determine the most appropriate rigging system for the theatre, then begin designing it and communicating weight carrying requirements to the structural engineer.

Stage Lighting Control System The extent and components will be based on the theatre's lighting needs and lighting equipment.

Stage Lighting Equipment and Accessories Specify the initial package of stage lighting based on the production style and types of productions planned. This will be influenced by any equipment the theatre owns and plans to reuse.

Stage and Acoustic Drapery Design and specify the stage drapery based on the theatre's needs and the acoustic drapery based on the acoustician's requirements.

Orchestra Pit and/or Stage Lifts Design and specify the equipment for orchestra pit lifts and stage lifts.

Orchestra Shell For theatres that plan to host symphony orchestras, design and specify an orchestra shell that redirects the sound headed into the wings and flyloft into the house. This work is done in collaboration with the project's acoustician.

Acoustic Reflectors We may use the acoustician's recommendations to design and specify acoustic reflectors over the house.

Theatre Planning FAQs

We have a longer FAQ about theatre planning here, but the three most common questions are answered below.

Why can't an architect design the theatre? Architects are responsible for the overall building, but do not design every element themselves. They hire a team of specialists that includes engineers, interior designers, landscape designers, and others. Theatres are highly specialized buildings that must meet the unique requirements of the theatre companies that use them. Space planning and designing the production infrastructure of a performing arts venue are best fulfilled by trained specialists such as theatre planners, acousticians, and A/V consultants.

When should we start working with a Theatre Planner? As early as possible! Theater planners can help theatre owners and architects evaluate their goals for a renovation or new building, and provide important information on feasibility, cost, scheduling, and more.

Who hires the Theatre Planner? Hiring a theatre planner depends in part on the owner and in part on the question of responsibility. Most large organizations such as universities or municipalities will expect the architect to assemble the entire design team, including the theater planner. Smaller organizations may not have established requirements in this regard. In some cases, theatre owners prefer to hire theatre planners separately from the architect to clearly establish that they are directly responsible to the owners.

The Theatre Design Team

As we’ve mentioned, an entire team of experts is required to design and engineer a performing arts theatre. The design team will include:

Theatre Planner who will understand the owner and/or user’s requirements and explain those requirements and their purpose to the design team. The theatre planner will also guide the space planning and adjacencies, design the seating layout, and design the theatrical systems.

Architect who will use the theatre planner's guidelines and space planning to develop and design the overall building. The architect will also coordinate the work of all other consultants, and may act as the interior desginer.

Acoustician who works with the theatre planner and architect to develop the shape and volume of the auditorium or house to optimize the acoustics. The acoustician will also advise on surfaces to absorb, reflect, or disperse sound, and will advise on keeping outside noise out of the theatre.

AV Consultant who will work with the acoustician on the placement and power of the speaker system. The AV consultant will also design the infrastructure for the sound, backstage communications, and video projection systems.

Engineers who will design the structural support for the building, the electrical distribution, the heating and cooling, the plumbing, the telephone/data, and all of the other infrastructure in the building.

Lighting Designer who will design the non-theatrical lighting and lighting controls throughout the building.

Owner and/or Users, who are the reason the building is being designed and constructed. Their input, especially in the early stages of design, is what establishes the requirements for the theatre’s size, its outfitting, and all of the spaces that surround and support the theatre.

The Performer / Audience Relationship

Theatre is storytelling, and theatres are machines that help tell those stories. The actor/audience relationship determines how stories will be told (presentational or environmental, for instance) and, to an extent, the types of stories that can be told. Therefore, the first consideration for any new theatre building is also one of the core elements of theatre production - the relationship between actor and audience. The spatial arrangement of stage and seating affects every other decision, from the extent of theatre systems such as rigging and stage lighting, to the director’s choices in arranging actors and scenery on stage.

Well-designed theatres, regardless of their form, have several important features in common. First, they support a type of intimacy and energy that is only found in live performance. They ensure the audience is comfortable and can fully experience the story being told without straining to see or hear, and that the performer is aware of the audience’s reaction to events as they unfold. Second, they provide an appropriate facility that supports the production. Stage equipment, backstage areas, and ancillary spaces must all be suited to the users’ needs. Some key elements of a good theatre are:

Audience members have clear sightlines and are close enough to the stage to read the performers’ facial expressions.

Performers feel an intimacy with the audience because the audience is close and fills much of the performer’s view by being arranged on sloped or tiered seating, and in balconies and boxes.

The HVAC system is quiet so the audience hears silence, not air conditioning equipment, during a play’s most intimate moments.

The acoustics and sound system are clear and bright, and the performers’ speech or singing seems to be coming from the stage, not from a public address system.

The stage is appropriately sized and equipped for the users and their production style.

Backstage spaces are efficiently organized, adequately sized, and properly furnished.

Audience amenities are properly sized and meet expectations.

With the above guidelines in mind, some of the preliminary information required to designing a new theatre can be discussed and determined. The results will suggest the most appropriate theatre form.

Theatre Forms

Proscenium Theatres

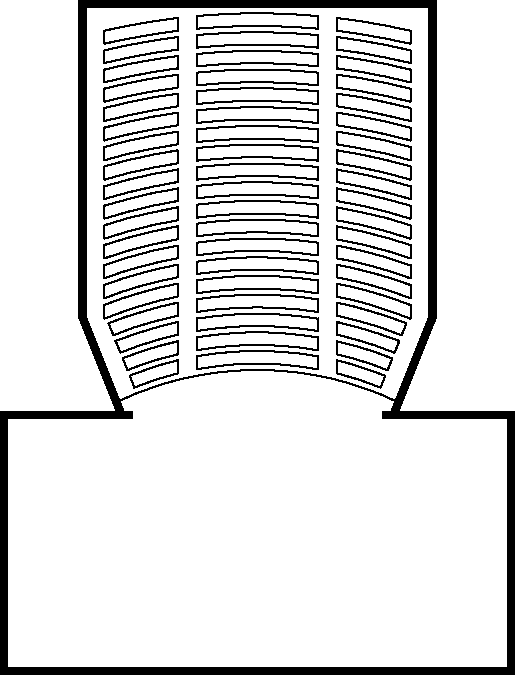

The most common theatre form today is the proscenium theatre. In a proscenium theatre the audience is arranged facing a common direction, toward an opening in a wall that separates the audience and the stage. The wall is the proscenium wall and the opening is the proscenium arch, which frames the audience’s view of the stage. The proscenium wall hides all off-stage spaces and activities to the sides and above the stage, thus helping to present a clean and controlled stage picture, and one that is more or less the same for the entire audience. A proscenium theatre often has one or more balconies and/or side boxes. These allow a higher seat count, and higher potential ticket sales, while keeping all of the audience members reasonably close to the stage.

The stagehouse (the part of the building that houses the stage) of proscenium theatres typically holds a counterweight or motorized system of steel pipes. The pipes, or “battens,” are hung parallel to the proscenium and placed every 6” or 8” for the depth of the stage. They provide a flexible suspension system for the scenery, production equipment (lighting, sound, and video), and drapery, including the house curtain.

Plan of Typical Proscenium Theatre, Orchestra Level

There are several variations on the proscenium that are well established and have their own name.

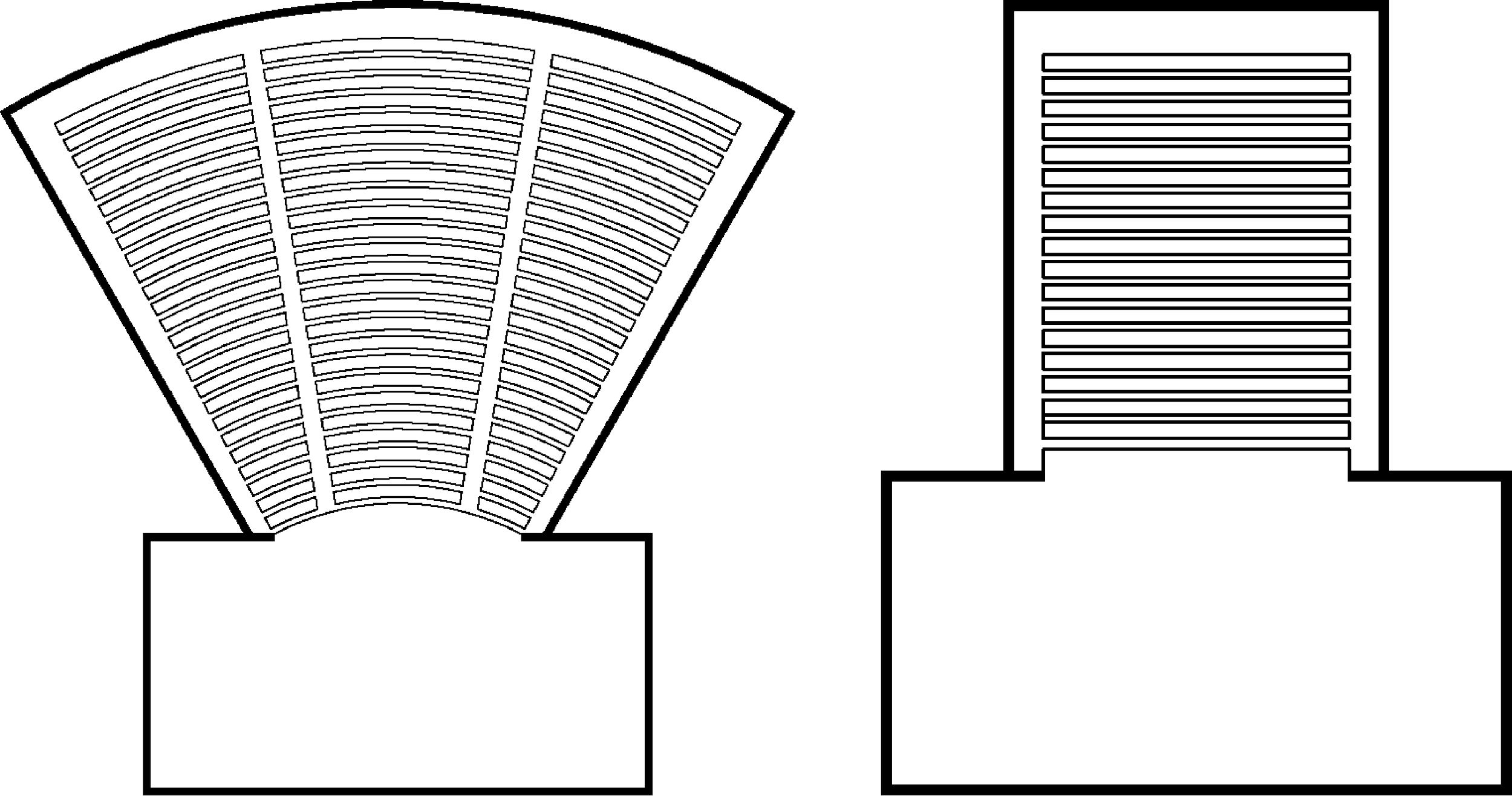

Fan Theatres

Fan theatres, or fan auditoriums, get their name from the shape of the auditorium. Popular in the 1960s, this form has fallen out of favor because the extensive seating on the orchestra level often replaced seating in balconies. This simplified construction, but the result was that too many audience members were too far from the stage to clearly see and hear the performance.

End Stage Theatres

End Stage Theatres are similar to typical proscenium theatres in that the entire audience is facing the stage from one direction. The differences are A) the audience is typically in straight rows facing straight the stage B) there may be no proscenium wall. In the latter case, the house and stage occupy the same rectangular space and the stage is simply a performance area at one end of that space. An end stage theatre is often the result of converting a relatively narrow existing building into a theatre.

Plans of a Typical Fan Theatre (left) and End Stage Theatre (right) (not to scale)

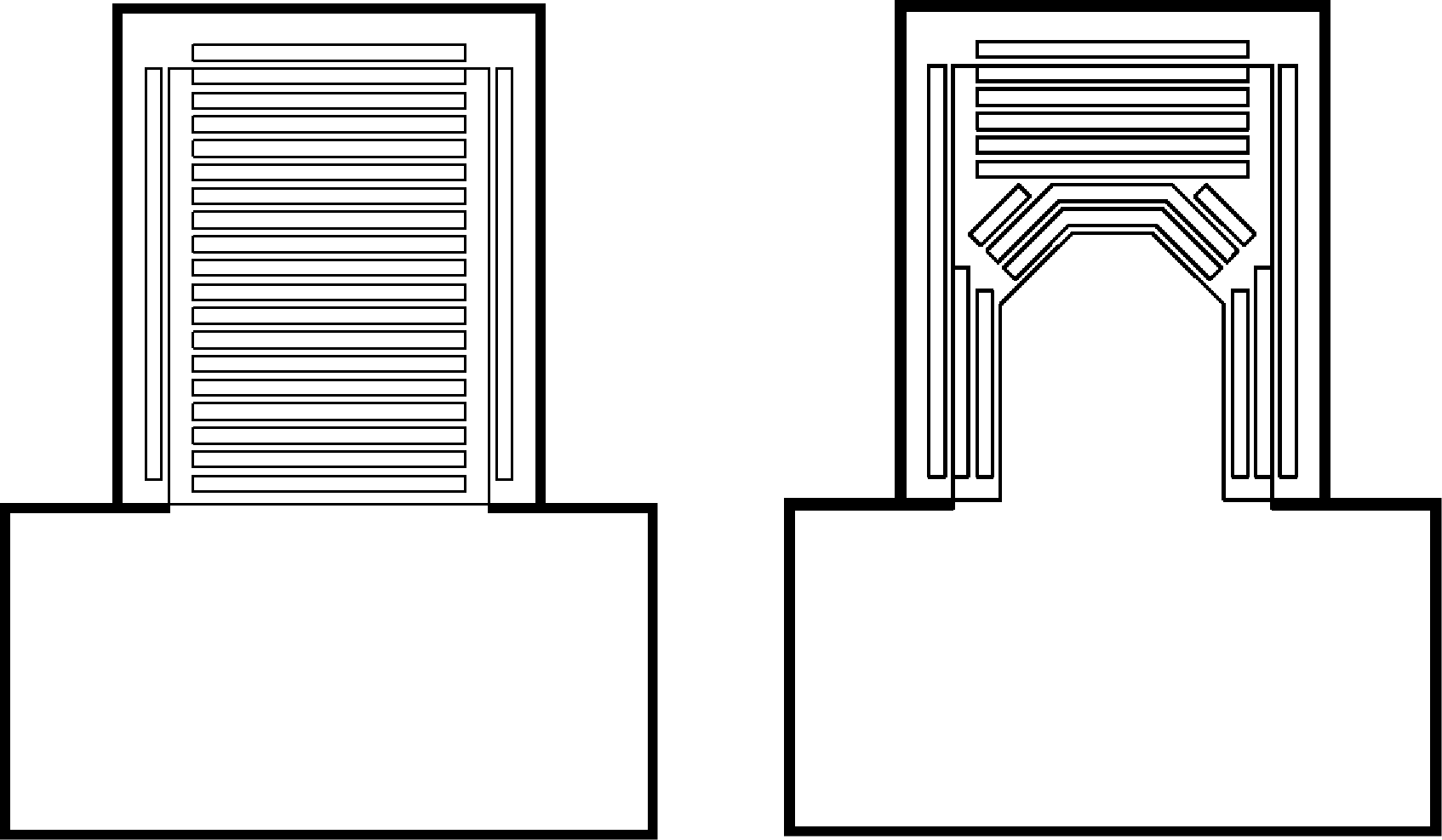

Courtyard theatres are a modern version of English theatres of the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries.. The auditorium is usually rectangular, with a sloped or tiered central seating area, a parterre (a raised seating area surrounding the orchestra seating), and one or two balconies over the parterre. In flexible versions of a courtyard theatre the central seating area can be reconfigured to create a thrust, arena, or alley stage.

Horseshoe Theatres

Sometimes synonymous with proscenium or courtyard theatres, horseshoe theatres are typically rounded at the rear of the house, giving them a horseshoe shape. They usually have a parterre one to three rows deep surrounding the orchestra seating and/or balconies, as in a courtyard theatre.

Plans of a Typical Courtyard Theatre in Proscenium (left) and Thrust (right) Configurations

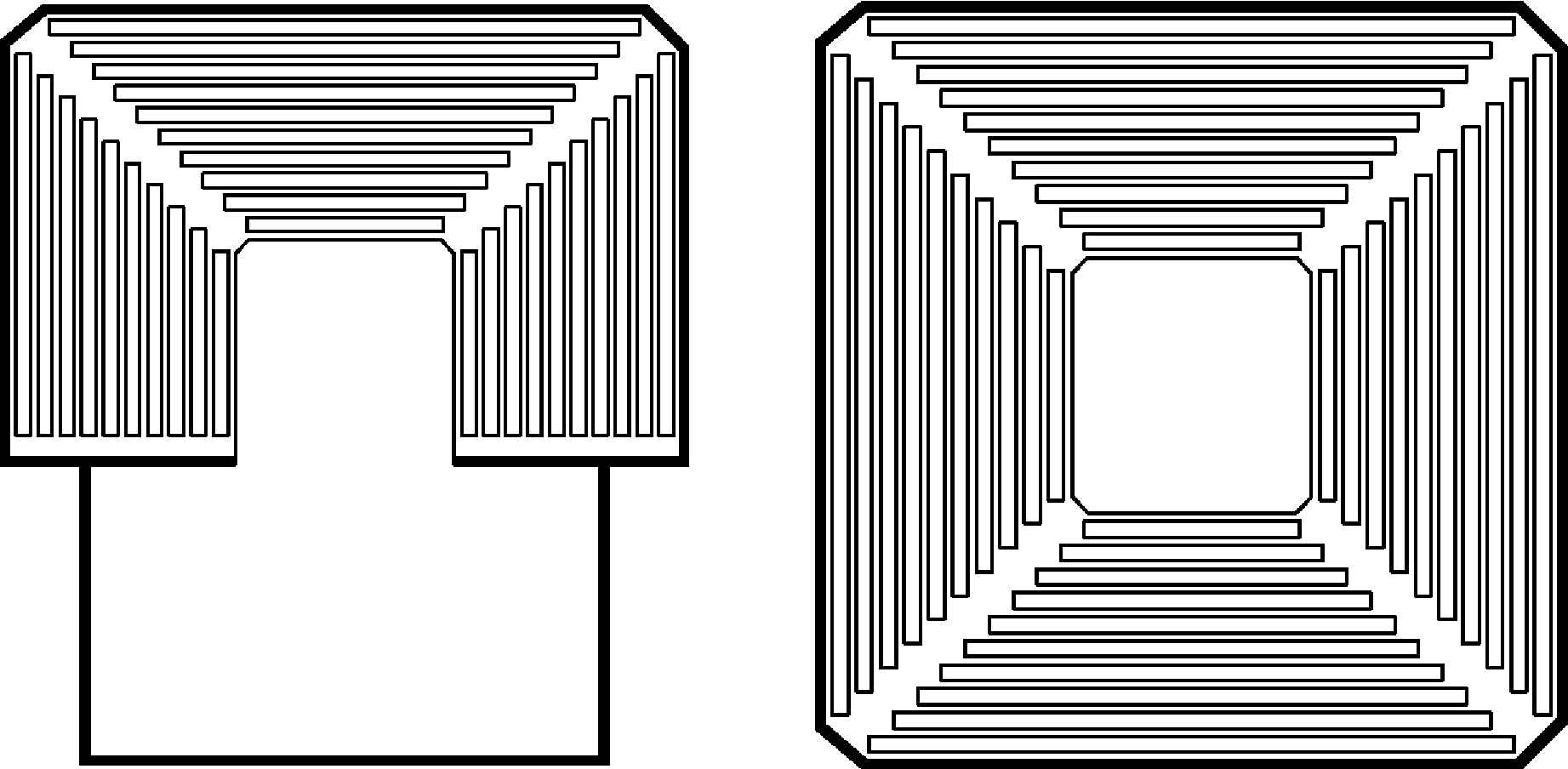

Thrust Theatres

In a thrust theatre the stage pushes out into the audience and the audience wraps around the stage. In doing so the audience is brought closer to the performer, and the performer is in a more natural, less presentational, relationship to the audience. The history of this type of theatre goes back to ancient Greece and Rome. Large scenic elements are confined to the side of the stage without audience. The rest of the stage must use low or open scenic objects that do not obstruct the audience’s view. With audience wrapping around the stage +/- 270°, actors, directors, lighting designers, and sound designers usually find thrust stages to be more challenging spaces than proscenium theatres.

Arena or Theatre-in-the-Round

Arena, or theatre-in-the-round, describes a stage that is completely surrounded by the audience. Tunnels or ramps, called vomitoria or “voms” give the actors access to the stage, usually at all four corners, from backstage areas. Arena theatres can only use scenery and props that are low enough that they don’t block the audience’s view of the performers. Actors must be seen and heard from every angle in an arena stage, making this the most difficult theatre for directors, lighting designers and sound designers to work in. Performers must be lit from all angles, and the actors need to change positions frequently so that no section of the audience is looking at a performer’s back for too long.

Plans of Typical Thrust and Arena Theatres (not to scale)

Alley, or Traverse, Theatres

Alley theatres place the audience on two long sides of a rectangular stage. They are rarely, if ever, purpose built, but can be set up within a courtyard or black box theatre.

Plan of Typical Alley Theatre

Black Box Theatres

Black box theatres provide users with the ultimate in flexibility. As the name suggests, they are open spaces, usually painted black, where neither the stage nor the audience location or size is fixed. Instead, the stage/audience relationship is part of the scenic design and is intended to complement the production. Large black box theatres may include a balcony for audience or equipment on several or all sides.

The Stagehouse

Properly sizing and equipping the stagehouse is critical to the success of any theatre. Major considerations include:

Proscenium Size The size of the proscenium should be in proportion to the size of the house, but there are a few rules of thumb. A proscenium less than 32’ wide is probably too narrow. 40’ to 45’ wide is very common. The height of the proscenium should be at least one-half the width.

Stage Size The stage needs to be deep enough and wide enough to hold not just actors and scenery, but actors and scenery that are waiting to go on or that have just come off stage. 15’ is a good starting point for the wings. 35’ of stage depth is usually adequate but more is better.

Stage Floor The stage floor should be made of wood so that scenery can be nailed or screwed into place. It should be somewhat resilient to cushion the impact of performers jumping or falling. If the theatre is dedicated to dance, a sprung wood floor is mandatory. The depth of the floor system can range from 3” for resilient flooring to 12” for a sprung floor. In some cases, the theatre consultant will specify several floor constructions to be mocked up and evaluated by the theatre users. In others, they may specify a pre-fabricated stage floor system.

Stage Height A good rule of thumb for professional theaters is that the stagehouse height should be 2 ½ times the proscenium height. Two factors can influence this consideration. First, in some locations local zoning will limit building height so the stagehouse will need to be shorter. Second, most building codes require a fire curtain at the proscenium if the stagehouse is higher than 50 feet. Fire curtains are not prohibitively expensive, but the cost may be a consideration in the final decision on stagehouse height.

Backstage Spaces

Backstage spaces can be divided into those that support the performers and those that support the performance. Each space has specific requirements.

Performer Support Spaces

Dressing Rooms Dressing rooms should be sized to accommodate the average cast, or slightly larger. Performers need to be seated at a well-lit mirror to put on their makeup. The makeup mirror should have a counter below it, and outlets nearby to power hair dryers, curling irons, etc. A bathroom with toilets, sinks, and a shower should be within the dressing room if possible. or nearby if not. Dressing rooms also need wall mounted costume racks or floor space for rolling racks.

The Green Room is a place for performers to congregate in a relaxing environment when they are not on stage. Sofas, upholstered chairs, and a table are commonly provided. A kitchenette is useful to prepare and hold food that is consumed on stage, and may be used as a lunchroom for stagehands during load-in and load-out.

Wardrobe and wig rooms are often adjacent to the dressing rooms for easy access by those responsible for wardrobe and wig maintenance.

The orchestra for musicals or dance often arrive already dressed for the performance, so they usually don’t need dressing rooms. However, they do need a place to gather before the performance begins. If musicals and dance are a regular part of a theatre’s season it’s a good idea to provide such a space.

Load-in and Load-out? Like other professions the theatre has its own language.

You can learn about these terms, and many others, in our Illustrated Theatre Glossary.

Production Support Spaces

Shops Theatres that produce their own shows are likely to need shops to build scenery, props, and costumes. Shops don't need to be part of the theatre complex, but it is easier if they are. Theatres that present touring acts don’t need to build much scenery, but they do need a space to maintain their lighting, sound and video equipment and to store unused equipment.

Loading Dock The theatre’s loading dock should be convenient to the shops, stage and the dressing rooms so everything brought to the theatre for a production has a clear path into and out of the building.

Offices The technical director, production manager, stage manager, and others with supervisory roles will need office space where they can review drawings, make calls, send emails, etc. These people may be able to share an office. A second office for tour managers is desirable if the theatre is presenting tours. The tour management will need a phone and internet access to contact the next venue, the hotel, their main office, etc.

Crew Room Like the orchestra, the stagehands need a place to gather and perhaps to change their clothes.

Storage A theatre that presents its own productions will quickly develop an inventory of scenery, props, and costumes they’ll want to keep for reuse in future productions. Storage space, either in the theatre building or at another location, is a necessity.

Front of House Spaces

Lobby The lobby is the gathering space for the audience before the performance and during intermission. Lobbies don’t need to be large, and many Broadway theatres don’t have one at all. Lobbies may be larger for opera houses and for companies that wish to use the space for other events or for rentals.

Ticket Booth Even with smart phones and print at home tickets, a ticket booth is still needed for people who don’t use those services, who want to exchange tickets or leave tickets for members of their party who are running late. Ticket booths should accommodate at least two active ticket windows.

Concessions Not all theatres sell concessions but if they do the offerings must be carefully considered. Soda fountains and beer taps require storage space for their cylinders and kegs, for example, and hot or cold food will require temperature-controlled holding equipment and may require a kitchen.

Restrooms The building code sets requirements for the quantity and distribution of restroom facilities in a performing arts building, but the quantity can be low. A good rule of thumb is to increase the code required quantity by 50%.

Sample Layout

Below is an example of the arrangement backstage and front of house spaces, as well as the adjacencies and interconnections between spaces.

What Building Codes Affect Theatres?

The short answer is, "All of them." It's important to remember that all codes are adopted at the city, county or state level. Even codes that have "national" or "international" in their title are just templates or models that local authorities can adopt as-is, or adopt with modifications. Therefore, it's important to confirm the codes in effect in the jurisdicion of each project. More specifically:

The local building code, which is usually a version or modification of the International Building Code (often called the IBC), which sets minimum standards for construction of safe buildings. The building code contains requirements and limitations affecting issues such as egress from all parts of the building, the number of exits and their width, fire resistant construction and sprinklers, aisle and row width, length, and clearances, and may contain requirements for accessibility.

The local electrical code, which is usually a version or modification of the National Electric Code (often called the NEC) sets minimum standards for the safe installation of electrical systems. The electrical code contains requirements for the feeder to dimmer racks, dimmer and relay racks themselves, outlets and lights at dressing room counters, portable cables and many more topics.

The local accessibility code, which is usually a version or modification of the Americans with Disabilities Act (usually referred to as ADA) or ICC A117.1, both of which set a wide range of requirements regarding the useability of spaces by persons with a range of disabiities. Topics that affect theatres include requirements for wheelchair spaces in the auditorium, assisted listening systems, and the length and steepness of ramps.

The Deptartment of Labor's OSHA General Industry Regulations 29 CFR 1910 sets requirement for things such as fixed ladders and catwalks.